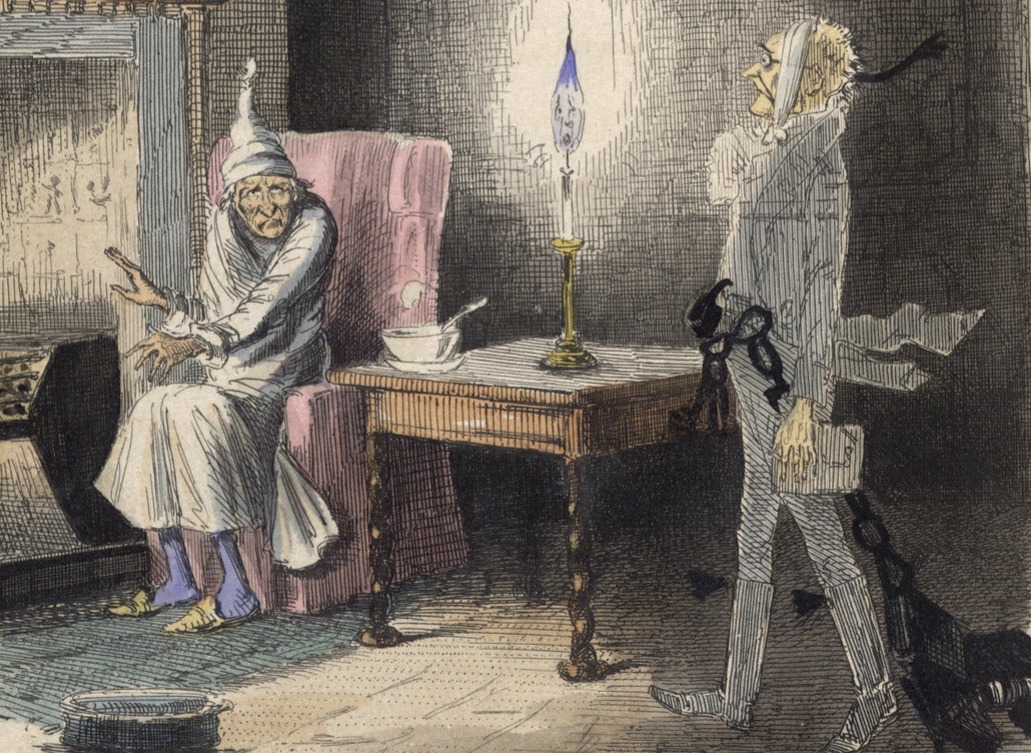

The redemption story of Scrooge is a deeply humanistic one, and in it, Dickens was constructing a broad and subversive church.

As a young child, my brother and I would be packed into the family car each year at Christmas and driven to Rochester, in north Kent. There, my father had an annual engagement that, to be quite frank, embarrassed the hell out of us both. In the boot of the car was a small suitcase, and inside that a tailcoat, watchchain and other faded garments. We’d arrive soon after sundown at Gad’s Hill Place, the final home of Charles Dickens, and within the hour, dad would be up on stage in the school hall in Victorian costume, gripping a lectern, his body pitched forward as he read to the audience his own rendering of A Christmas Carol. We, meanwhile, slid ever deeper into our seats.

The voices of the many characters – gnarled and guttural for Scrooge, weak and whiny for Tiny Tim – I remember well. He executed them brilliantly. I also remember the odd gushing fan who’d greet him like a rock star once the reading finished. What I wasn’t of course aware of was the significance of the text itself. To me, it was just a Christmas story. The characters were richer than those of your average tale, and the story had a better developed moral arc than most. But it was just another Christmas story.

Only later did the subversive quality of A Christmas Carol, published in December 1843, come into view. Like several of Dickens’ other works, the book electrified much of Victorian Britain. But it did so for reasons that have been largely forgotten. The origins of A Christmas Carol had nothing to do with Christmas; it arose from an idea Dickens had earlier in 1843 to issue a political pamphlet, “An Appeal to the People of England on behalf of the Poor Man’s Child”, to protest against the exploitation of children sent to work in mines and factories. He was also exercised by the condition of children attending London’s Ragged Schools – free institutions for the poor that had been established by charities. Should children be given so much religious instruction in circumstances where the basic needs of food, drink and clothing seemed so much more urgent to address? “To impress them, even with the idea of God, when their own condition is so desolate, becomes a monstrous task,” he wrote in a published letter.

Dickens shelved his first idea of the “Appeal”, and decided instead to reshape it into a short story and then to link that story with Christmas. The “Poor Man’s Child” became Tiny Tim; Victorian society’s spirit of callous laissez-faire was embodied in the grasping misanthrope Ebenezer Scrooge. It was an extraordinary success: 6000 copies sold in one day.

A secularist Victorian bible

“Blessings on your kind heart,” the Scottish literary critic Francis Jeffery wrote to Dickens soon after reading the short book. “You may be sure you have done more good by this little publication, fostered more kindly feelings, and prompted more positive acts of beneficence, than can be traced to all the pulpits and confessionals in Christendom since 1842.”

A Christmas Carol was greeted at the time, informally at least, as something of a secularist bible – or, as Paul Davis writes, “the first gospel in the ‘secular scripture’ of Victorian fiction”. Dickens located the story in a smog-filled London at a time when cities, according to the American critic J. Hillis Miller, were “the literal representation of the progressive humanization of the world… The way in which many men have experienced most directly what it means to live without God in the world.”

That distancing from Christian worship is reflected in the book. Despite occasional mentions of “Our Founder”, as well as the fact that Dickens was a practising Christian himself, A Christmas Carol steers clear of theological evangelising. The redemption story of Scrooge is a deeply humanistic one, and as such, the book appealed to both churchgoers and agnostics. It therefore stood out at a time when obsession with Christianity was pervasive in the literary world. By the time of Dickens’ death, half of all monthly periodicals and books were religiously oriented, despite the fact that religion was waning in British society more generally as a result of the rise of evolutionary science and the historical criticism of the Bible that would come a decade or two later.

“I am sure I have always thought of Christmas time, when it has come round – apart from the veneration due to its sacred name and origin, if anything belonging to it can be apart from that – as a good time: a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time,” Scrooge’s nephew says early on, shunting the religious origin of Christmas into a passing parenthesis and instead emphasising the humanist value and meaning of the festivity. “The only time I know of, in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts, freely, and to think of people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys.”

I didn’t understand, as a child, that in this Christmas tale, Dickens had nailed together the structural edifice of a broad church, one that took ownership of charity away from the pious and made it a public moral duty. His belief was that responsibility for the unfortunate should be democratised – it was everyone’s to share. It’s a nice thing to remember my father using Christmas to bellow this same message from the lamplit stage.