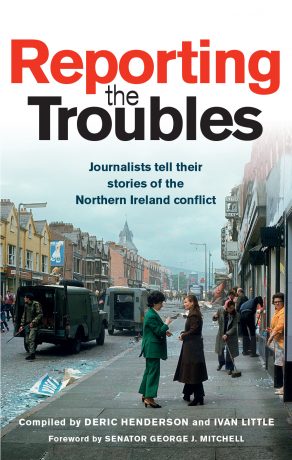

On 5 October 1968, a banned civil rights march in Derry led to clashes between the Royal Ulster Constabulary and protesters, sparking rioting, disorder and violence across Northern Ireland. This was the start of the Troubles. The violence would continue for 30 years. In “Reporting the Troubles” (Blackstaff Press), editors Ivan Little and Deric Henderson have gathered together a collection of previously untold stories from 68 journalists who covered the Troubles. With contributions from household names including Kate Adie, Martin Bell and Eamonn Holmes, the book aims to provide social history and a chance to reflect. Here, Henderson and Little discuss the project.

Why did you decide to collect journalists’ stories?

Even though Northern Ireland is in a new place in the aftermath of the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, dealing with legacy issues has been a source of much debate and controversy, as well as being hugely divisive within the Protestant and Catholic communities. Several efforts and many initiatives have been, and continue to be considered, but there are no signs of coming anywhere close to an agreement. So how would this book sit within the ongoing narrative?

5 October 1968 is generally accepted as the date when the Troubles started in Northern Ireland, and 50 years later, we thought maybe this was an appropriate time for the journalists to look back and reflect on their time working through the worst of the violence. They had reported for various print and broadcast outlets for all those years, but they had never publicly revealed their own thoughts and emotions about the terrible events they covered and the people they met.

Martin Cowley, then of the Derry Journal, who went on to work for the Irish Times and Reuters, was in Derry on the day police clashed with Civil Rights demonstrators. He was the first journalist we approached and he immediately agreed to embrace the project just before Christmas 2017. After that, we approached journalists in Belfast, London and Dublin, and with one or two exceptions, they all thought this story telling process was a worthy and unique idea.

What role did these journalists play throughout the 30 years of the Troubles?

All of them had played significant roles throughout the Troubles at a time when there wasn’t 24/7 coverage, access to state of the art technology and long before the arrival of social media. Back then journalists relied heavily on face-to face contact with government officials, security chiefs, and sources within loyalist and republican terrorist organisations. But they also had to be careful not to abuse their positions, or allow their positions to be undermined by those they dealt with. The path they followed was always a narrow one

What were the challenges of reporting on the Troubles?

It was always impossible to detail the full facts of every story, but achieving accuracy in everything reported was absolutely critical. It was never easy, and although one of us – Deric Henderson – never faced any direct intimidation, many others, including [the other half of our editorial team], Ivan Little had to deal with serious and direct threats on their lives. Ivan Little worked for Ulster Television and for ITN, and received a number of death threats. One of them came from a loyalist organisation, the Ulster Defence Association, in a phone call from a paramilitary leader who bizarrely assured him that there was “nothing personal” in the death threat, claiming it was aimed as a warning to the news organisation he was working for.

One journalist, Martin O’Hagan of the Sunday World, was murdered by a loyalist paramilitary organisation, the Loyalist Volunteer Force. He was shot dead because he constantly exposed what the organisation were doing, not only in relation to their sectarian attacks on Catholics but also because he shone a light on their activities in terms of racketeering and drugs. A colleague tells Martin’s story in the book.

Another Sunday newspaper journalist, Jim Campbell, writes in the book about how he came perilously close to death in another loyalist gun attack. Again, Jim’s reporting about the loyalists’ gangsterism rankled with them. He survived the shooting but the terrorists wrote “We’ll get you next time Campbell” on the gable walls. Thankfully, their threats were never carried out.

Did journalists do a good job of reporting the Troubles?

We think the overwhelming majority of journalists can look back on their time in Northern Ireland satisfied that they did their best in enormously difficult and challenging circumstances, especially those who were born and brought up there, who had to struggle with a deep, emotional attachment. They were not foreign correspondents heading to far off places, but reporters who found themselves working within their home environment and a seriously divided community.

That represented massive challenges, because no one owned the story of the conflict. Journalists’ contributions were no more, or no less important than the stories of the many who lived through the horror and hell of what Northern Ireland used to be. It took its toll on all our lives. Apart from the challenges and demands, it could be hugely stressful trying to maintain some degree of sanity amid all the anguish and sadness.

There is still a lot of hurt, a lot of grief and an awful lot of unfinished business, especially when attempting to deal with the past and all the unresolved legacy issues. But this book serves as a timely reminder of how the men and women of the Fourth Estate went about their business.

How has the legacy of the Troubles continued to reverberate in peacetime?

The Troubles haven’t disappeared completely. A number of dissident Republican groups have shown that they still have the capacity to kill prison officers and attack police personnel. But there is no doubt that the threat is nowhere near as bad as it was 20 years ago. However, the families of the victims of the Troubles are still demanding justice and closure. A number of initiatives have been launched to give them answers as to who killed their loved ones and why. But no satisfactory solution to the legacy issue has been agreed upon and there’s a sense of frustration among many people that there will never be a resolution. Of late, former members of the security forces have also claimed that the re-investigation of past killings has concentrated too heavily on them and insufficiently on the terrorists.

Around the UK, do you think we engage sufficiently with the very recent history of the Troubles?

Undoubtedly not. But people across the water are not the only ones who don’t really want to know, to remember what went on in Northern Ireland and indeed in Britain, where the terrorists also held sway. In Northern Ireland, while many people are actively pursuing justice and answers, many others shy away from reliving the nightmare. That is particularly evident among many young people who have been closeted away from the dreadful realities of the Troubles by parents who think it’s better to spare them from knowing the full, awful extend of the violence.

We hope Reporting the Troubles will allow younger people to realise just what did go on, and why we must be determined not to allow the past to repeat itself in the present and in the future.

What do you make of the lack of attention given to the Irish border question during the Brexit campaign?

It’s hard to say that the border has been ignored. But it was definitely put on the long finger in the early discussions, and only in recent months has it become a priority. The main problem is that the border looks to many people here as close to an impossible dilemma as one can get. There’s also been a sense that the negotiators are bound to come up with an answer in the end, because the alternative of the hard border is too difficult to even comprehend. But as time marches on, the likelihood of a solution appears to recede with every passing day.

Do you anticipate a resurgence of conflict in Northern Ireland?

There is certainly no appetite for a replay of the violence. The last 20-odd years of peace have hardened the resolve of people that there should never and could never be a return to war. But complacency is dangerous. The lack of an effective government at Stormont and the uncertainty over Brexit have the potential to muddy the waters and heighten tensions between the two communities.

Are there particular lessons that we should take from this book?

We hope the book will show people, old and young the senselessness and horror of violence that should have no part to play in any society. But it would be naïve to expect that people in conflict zones, which seem to increase in numbers around the world every year, will use the book as a template for journalistic standards. We can only say that having worked on the frontline in Northern Ireland for most of our working lives, the responsibility and sensitivity demonstrated by the vast majority of journalists covering the Troubles has been exemplary.