Máiría Cahill bravely breaks the silence around allegations of sexual abuse in the IRA

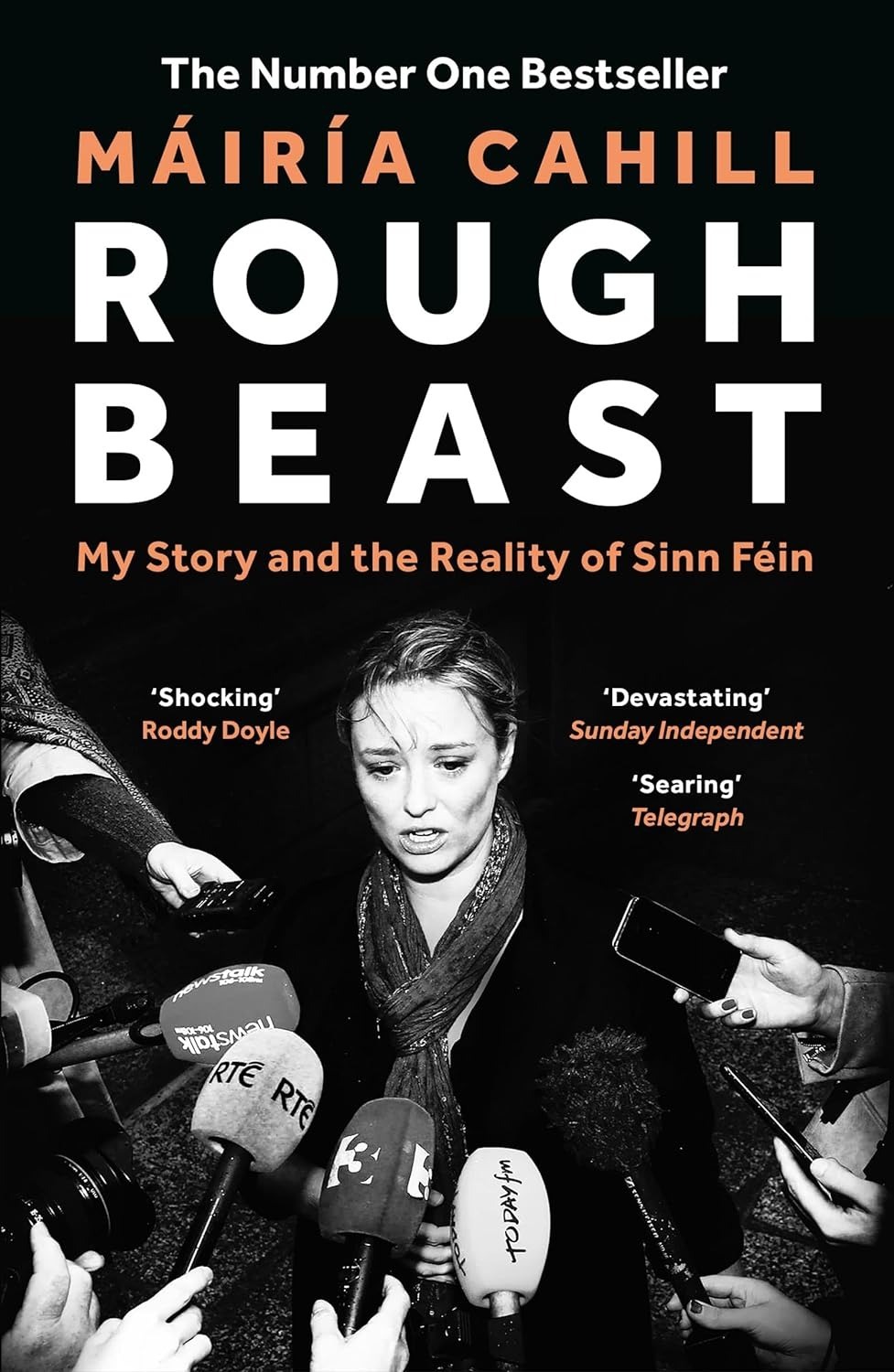

Rough Beast: My Story and the Reality of Sinn Féin (Bloomsbury) by Máiría Cahill

Máiría Cahill began her political life as a teenager. She belonged to one of west Belfast’s most venerable republican families, and so was considered Irish republican royalty. The events described in her book Rough Beast – but most of all her personal courage and unwillingness to be silenced – have since turned her into Sinn Féin’s most effective and feared modern-day critic. The book’s title harks back to Yeats’ famous poem “The Second Coming”, conjuring the collapse of civilisation, where the “rough beast” in those chilling last lines “slouches towards Bethlehem”. It is also, more specifically, both Cahill’s IRA alleged abuser and the movement that closed ranks around him.

Cahill was born in 1981. Her great-uncle, Joe Cahill, was chief of staff of the Provisional IRA in the 1970s. By the late 1990s Máiría was national secretary of Sinn Féin’s youth wing, working closely with republican leaders. Given her lineage and obvious capabilities, it is entirely plausible that – but for the horrific events described here – she could have been Sinn Féin’s leader by now. What changed her life trajectory was her experience of, she alleges, being sexually abused as a teenager by a prominent member of the IRA in the 1990s; being subjected to an internal IRA investigation that forced her to confront her accused abuser; and ultimately her extraordinarily brave decision to break republican omertà and speak out publicly.

Although two other women also say they were sexually assaulted by the same IRA member, the complication of proving IRA membership was one factor that sabotaged a successful criminal prosecution of the alleged perpetrator, who denies the claims. A report in 2015 concluded that the Public Prosecution Service in Northern Ireland had failed all three victims. This gained Cahill a public apology from the Director of Public Prosecutions, but no real justice. Meanwhile Sinn Féin’s response to the Cahill case has been to disparage her privately whilst eventually, under huge public pressure, issuing half-hearted and heavily caveated apologies. But its behaviour in this case is all of a piece with its wider attitude to past wrongs: those such as Bloody Sunday involving British state culpability should be investigated and exposed, but its own past actions, and those of the IRA, should be shielded from scrutiny.

As well as a brave and penetrating critic of Irish republican politics, Cahill is a brilliant and powerful writer, and I hope this book will not be her last. Her account sheds an unforgiving light on the internal culture of Sinn Féin and the IRA. We tend to think of Irish republicanism as a political and paramilitary movement, but it is also a dense network of interconnected families whose loyalties are not simply to a cause but to each other. Anyone who confronts this closed and secret world needs moral courage and determination, and physical courage, too: Cahill was, after all, dealing with a group of professional killers. The outside view of the Northern Ireland Troubles sees the Good Friday Agreement as a watershed with paramilitary disarmament following shortly after – but this book shows how paramilitary power persisted in west Belfast long after the peace process was supposedly well advanced.

As well as being an outstanding memoir of Cahill’s personal story, this book also has contemporary importance. Already in power in Northern Ireland, Sinn Féin seems increasingly likely to enter government in the Republic, probably as the largest party (see page 30); its anti-austerity messaging understandably resonates well with younger voters. Cahill’s book raises profound questions about how safely Irish democracy can be entrusted to Sinn Féin, however. A few decades ago, part of the Irish left disavowed republican sectarianism and mafioso politics, but with Sinn Féin these strains are never far below the surface. Can they be trusted to lead a democracy? In my view this is the fundamental question posed by this impressive book, and on the evidence here it has to be answered in the negative.

This article is from New Humanist’s summer 2024 issue. Subscribe now.