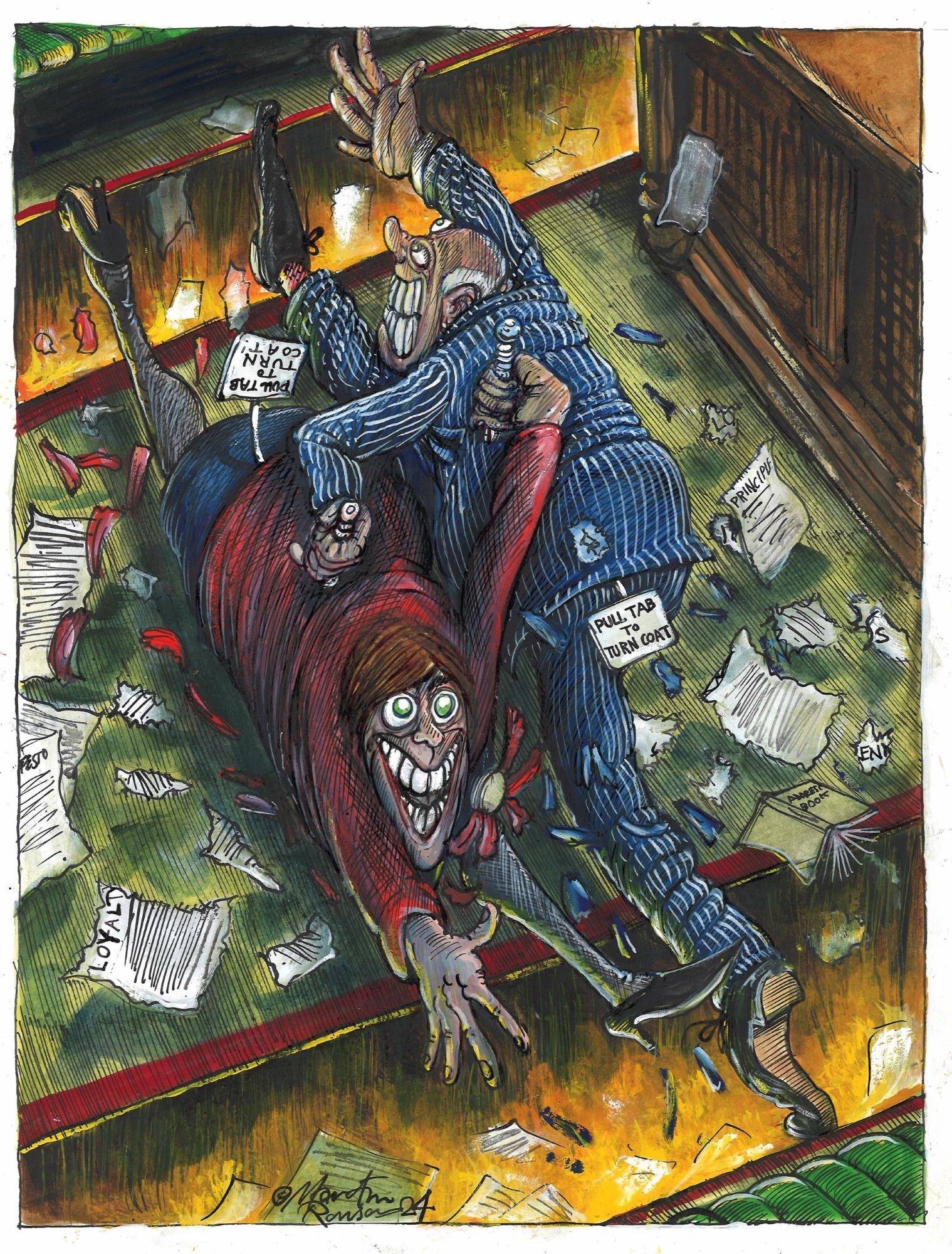

British politics has never been so rife with defectors. Why does the feeling of being betrayed provoke such a powerful response?

So I spread my robe over you and covered your nakedness, and I entered into a covenant with you by oath – declares the Lord God; thus you became Mine … But confident in your beauty and fame, you played the harlot

– Ezekiel 16:8-19.

The general election in July, which saw the Labour Party gain a huge majority, also saw a huge shift in voter allegiance – but not to or from Labour itself. In a sense, Sir Keir Starmer simply set his party up as a still centre around which the dance of a volatile electorate took place. This dance seems set to continue. But it is not just the electorate that has shown itself prepared to shift allegiance. The last year has also seen an extraordinary number of MPs change parties.

On 30 May – the day parliament was dissolved before the election – the outgoing Conservative MP for Bolton North East, Mark Logan, announced that he would be joining the Labour Party. Rishi Sunak’s Tories were, he said, “unrecognisable” from the party he had joined a decade earlier. He became the fourth Conservative MP to defect to Labour in the 2019-24 parliament, following Christian Wakeford in July 2022, Dan Poulter in April 2024 and Natalie Elphicke in May 2024, three weeks before Logan.

Each was not only denounced as a traitor by the party they left, but treated with some suspicion by members of the party they joined. (Elphicke was regarded as particularly suspect given some of her previous views on immigration and, indeed, the Labour Party.) Of these, only Wakeford, in a safe Labour seat, remains in parliament. Meanwhile Lee Anderson – deputy chairman of the Conservative Party as recently as February 2024 – defected to Reform in March, becoming their first MP. He was joined by four more in July, including Reform leader Nigel Farage – who is himself arguably a defector from UKIP.

Starmer’s bet was that the most appealing offer in a time of such volatility was to emphasise stability and discipline. It has paid off, for now. We have already seen a ruthless streak in his dealings with the left of his party – witness the excising of Jeremy Corbyn. But given that Corbyn, pushed out of a party he once led, retained his seat as an independent, might other Labour members follow suit in future, making their own decision to jump?

Changing parties has a long history in the UK, ever since the “tall, thin and haggard” John Grubham Howe quit the Whigs in 1698 to become a Tory during the joint reign of William and Mary. Howe, who was found guilty of wounding one of his own servants, had been dismissed from his role as vice-chamberlain to the Queen. Inevitably, his initial defection was greeted with cries of “traitor”, and King William exclaimed that had they been of the same station he would have challenged him to a duel.

Howe set the path for what has been a venerable if seldom venerated tradition in UK politics. Since 1979, some 202 UK MPs have left their parties while retaining a seat in parliament. However, in 56 per cent of these cases the move was not voluntary – they, like Corbyn, had the whip removed, or were suspended, and in many of these cases they later rejoined the party. The rest resigned willingly, but usually not to join the other side. It’s far more common for defectors to sit as independents.

In Britain a member of parliament ultimately represents their seat, not their party, so there is no imperative to resign on changing allegiance. A constituency may elect a Tory and end up with a member of the Labour Party or vice versa. The voter has no say, and expressions of anger among the electorate are not uncommon, especially where voters had chosen a party rather than a personality.

There are more or less audacious forms of defection. The act of leaving one party to form a new one remains rare. Perhaps the most famous case is the formation of the Social Democratic Party in 1981, when the so-called “Gang of Four” – Roy Jenkins, David Owen, Bill Rodgers and Shirley Williams – and 28 other Labour members left to form a more centrist party, which would eventually join forces with the Liberals in 1988 and become the Liberal Democrats. The short-lived Change UK, which lasted a mere 10 months in 2019 and saw all of its members lose their seats, is a more recent example.

Rarer still is the act of leaving one of the two major parties to join the other – let alone from the ruling party to the opposition, as Logan, Elphicke, Wakeford and Poulter did. Almost invariably, it is a decision that leads to defeat – the Labour politicians Alfred Edwards and Ivor Bulmer-Thomas, who left the party to join the Conservatives in 1948 in protest against the nationalisation of steel, were both heavily defeated in the 1950 general election. Edwards stood again in 1951, in another seat, and lost again.

More successful was the former trade union official Reg Prentice, who left Labour in 1977 to join the Conservatives and became a minister of state at the Department of Health and Social Security in Margaret Thatcher’s government. Despite his own history in the union movement, he saw Labour as being in the thrall of militant leftists, and felt he could no longer stay in the party. Alan Howarth, who left the Conservatives to join Labour in 1995, and was re-elected as a Labour MP in 1997, is the only member since 1979 to serve as a minister for two different parties. In his latter role, he served alongside Shaun Woodward, who had left the Conservatives to join Labour in 1999.

In each case the fact that the Labour Party was in the process of becoming the government may not have been a coincidence. As the then Tory leader William Hague told Woodward, “You have left a party whose members have given you their loyal support. You have done so for reasons not of integrity or of principle, but for your own careerist reasons.”

If so, Woodward achieved his aim, serving for three years as secretary of state for Northern Ireland. But not everyone accepted him with open arms. Notably, Labour’s Chris Mullin wrote in his diary that hearing Woodward on the radio “promising to be a champion of the poor and downtrodden made my flesh creep.” Similar sentiments were expressed about Elphicke’s defection by current Labour supporters. (Elphicke is no longer an MP, as she did not stand for re-election in July.)

In parliament and in the electorate the duplicity – “treachery” even – of changing parties tends to produce this sort of visceral reaction. To change one’s party is not like changing one’s hat. It is also, as Hague noted, a rejection of one’s colleagues. But more than this, it calls into question one’s own beliefs, and the beliefs of those around you.

In his 2017 book On Betrayal, the philosopher Avishai Margalit explores what it means to betray someone or something. Not the practicalities of doing so – that is easy enough – but the deeper meaning of betrayal. And why does being betrayed lead to such a powerful emotional reaction? Margalit identifies four main forms of betrayal – political, personal, religious and class. The first of these finds its apotheosis in treason, the second in adultery and the third in apostasy, where one defects from one religion to another, or to none at all. Class betrayal is more nebulous, but as with the others provokes emotional reactions (and, in the UK in particular, a vast amount of energy is spent by individuals attempting to claim that no such betrayal has occurred).

As Margalit notes, the social taboos once associated with adultery and apostasy have weakened – in fact, apostasy is now seen as a basic human right in most western countries (although globally it is still punishable by death in at least 10). While adultery is now treated with more leniency on a legal level, “cheating” by “breaking the marriage vows” remains a powerful and disturbing occurrence on a personal one. To be betrayed by one’s partner with another introduces a wound into a relationship that is difficult and often impossible to heal. What is it, Margalit asks, that causes such hurt? In his earlier work The Ethics of Memory, Margalit had identified two types of ethical relationships, which he described as “thick” and “thin”. “Thick” relationships are those which have the greatest hold on us, and which we have the greatest duty towards – relationships we have with the members of our “tribe”, family, nation, circle of friends and of course our “life partner”. These are individuals with whom we share not only our space, but what Margalit calls our “memory”.

And here memory is not simply “recall”, but the building blocks of a shared cultural space. Our interactions add to this space as we grow cultural references together – a couple or a family will have a set of codes, beliefs and connections, which they share and which are exclusive to them. A “thick relationship” is not a “possession” but a bond.

This bond is, for Margalit, “belonging”, which is “an orientation on the world, a home” – a shared space of values and ideas in which we dwell. This idea of “home” is crucial – by existing within this space we feel a sense of safety. Not all ideas and memories within a relationship are shared, of course, but those that are allow us to exist in a space that centres us and keeps us safe. We build various “homes” – our relationships, our families, our friends, and, yes, our political affiliations.

Betrayal, argues Margalit, is not simply an attack on trust, but something more fundamental. It is an attack on our “thick relationship” – and therefore on our home in the world. The betrayal that occurs in the case of adultery, for instance, “isn’t leaving a relationship but breaking it – and breaking it in a way that hurts, that leaves the other or others vulnerable, frightened, alone, at a loss.” Worse, it is not only the future of the bond that is attacked: betrayal “provides the betrayed party with a good reason to re-evaluate the meaning of the thick relation with the betrayer.”

All betrayal requires a third party, and if that third party also shares a thick relationship with the first party, two emotional homes are destroyed. If the basic model of betrayal is “A betrays B with/to C”, then “A betrayed B with her best friend C” is a double betrayal. There is a cost for the “betrayer” too, which, for obvious reasons, tends to be greeted with less sympathy.

These days religious and political homes tend to be less central to most people than personal homes, but this model of betrayal still holds. We see the extreme example of this in cults, where huge psychological damage is done in the act of leaving. One does not just lose the object of one’s previous devotion, but one’s whole world. Religions and especially cults recognise this – the apostasy of a believer threatens the entire “church” by attacking the world it has built. (This is why, for instance, in Christianity the “lost sheep” that returns to the fold is so valued.)

Here the religious model mirrors that of the domestic. In his first book, Idolatry, Margalit noted the way that the Bible uses metaphors of romantic betrayal to describe what it is to “cheat” on God. The passage from Ezekiel at the start of ths article is the standard form – at a time when marriage was a financial arrangement as much as a romantic one, to leave is to become a whore.

And so to political parties. Those who are members of a party must, to a greater or lesser extent, “buy into” a certain creed, while a great deal of political life is spent on meetings, organising, rallying, attending constituency events, fundraising and so on. A political party is a “home” in Margalit’s sense (and some of the arguments that go on within one closely resemble those that occur in the domestic space).

To leave a political party is, therefore, to betray a thick relationship. And to join an opposition party is to reverse a second relationship between the rival parties themselves – a thick relationship which may be based in antagonism, but which is nonetheless proximate and deep. To leave one home and choose another (and to then remain in the shared space of the political world, especially when some of that space, such as the Houses of Parliament, is very intimate indeed) leads to the sort of visceral reaction Mullin felt about the defection of Shaun Woodward. The flesh can creep. And unlike in some personal relationships, there is little motive or desire for “forgiveness”.

As the philosopher Josiah Royce put it in 1913: “The traitor is one who has freely embraced a cause and joined with a community of grace in service of that cause, but who then culpably commits some act that undermines the cause and the community. Such a betrayal is but one step away from moral suicide.”

Yet our ideas of loyalty and treachery have shifted over the years, and will no doubt keep evolving. In these times of political flux, finding a home in a party is becoming more complicated. We may look back at the general election of 2024 as a turning point in Britain. It will be interesting to see how many politicians of all stripes are prepared to take the risk and seek a new home in future, and whether our reactions will still be as visceral.

This article is from New Humanist’s autumn 2024 issue. Subscribe now.