Cristina Rocha tells the story of how the the "cool" global megachurch Hillsong gained influence in Brazil

Cool Christianity: Hillsong and the Fashioning of Cosmopolitan Identities (Oxford University Press) by Cristina Rocha

Hundreds of wide-eyed teenagers bounce up and down in a blacked-out auditorium chanting, “DA-DA DA-DA-DA-DA.” Searchlights flail and a band clad in baggy trousers and jumpers drives the crowd into a frenzy. Is it a school disco? Is it an indie gig? It certainly doesn’t seem like a church. The YouTube clip shows Friday youth night at Hillsong Church, Sydney, Australia. Before the spectacular fall from grace of some of its leaders began in 2020, Hillsong was a cultural and business phenomenon. Established in 1983, the Pentecostal mega-church put down roots in cities right across the globe.

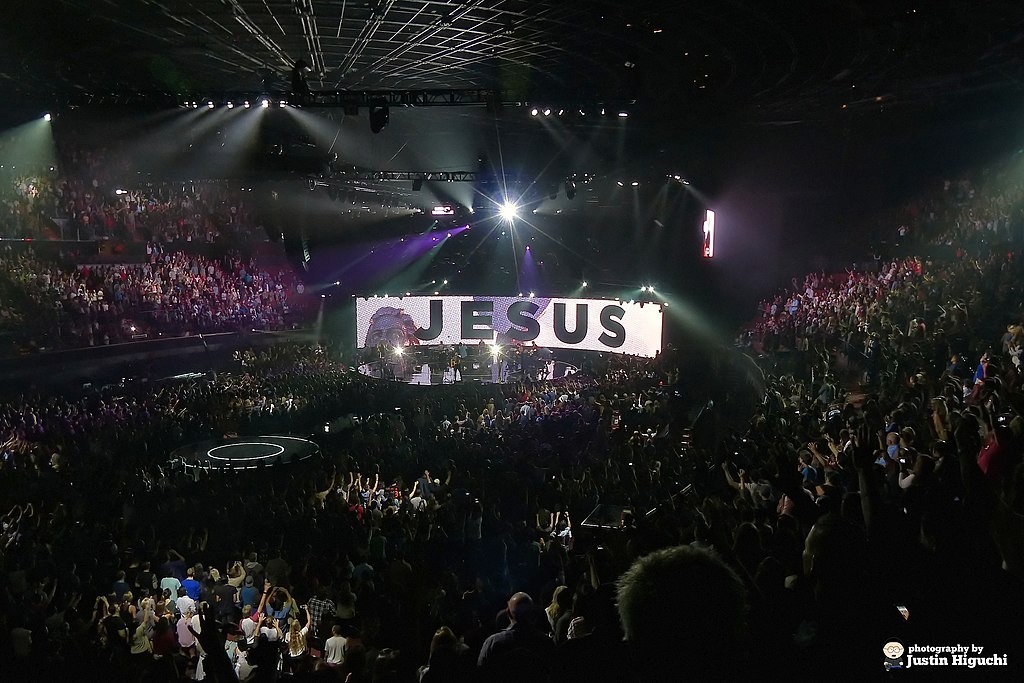

In Cool Christianity, Cristina Rocha’s interest is in the cultural and the social rather than the theological. She considers the appeal of Hillsong as a hip, young product of the global north aimed at educated middle-class youth in the global south, with particular reference to her native country, Brazil. Hillsong is a space where the sacred meets the spectacle. Hip pastors in ripped, skinny jeans and leather jackets preach to clean, young, well-to-do audiences in vast, darkened auditoria. Towering screens display rapid-fire video montages. Light shows and rock music ramp up the emotions. The performances are captured as sophisticated multi-camera shows for online distribution. Hillsong, as one church member puts it, mirrors the highest production values of Broadway or London’s West End.

The church’s founder and former senior global pastor, Brian Houston, said: “Churches are usually old, boring, irrelevant and empty. I always thought church should be enjoyed, not endured.” Houston is an engaging character with a fine line in self-deprecating humour, but his weakness and hypocrisy ultimately led to a global scandal involving allegations of exploitation and abuse that resulted in a spectacular falling to earth.

But the disgrace that drew Hillsong to the attention of the world’s media presents a distraction to Rocha’s central project. Her focus is on a section of Brazilian middle-class youth who feel alienated from the restrictions of a corrupt, authoritarian society riven by class and racial divides. These young people are drawn to the promise of moving away from their Brazilian identity as part of the “developing world”, towards a cosmopolitan world citizenship.

Brazil is traditionally a Catholic country but the Protestant churches have grown to encompass around 30 per cent of the population. A large majority of these are Pentecostalists. Pentecostalism has a strong base among the impoverished black community, but is generally viewed by the middle classes as crude and primitive. These churches practise the casting out of demons and “prosperity theology”, promising an abundance of material goods in return for cash contributions.

Hillsong offered a quite different approach. It has spread its message across the world primarily through recordings of Hillsong United, the church’s praise band that uses modern anthemic rock to sing about the need for individual salvation. This emphasis on celebrating a personal relationship with God helped build a global fanbase for the band and for Hillsong’s celebrity worship leaders.

Rocha describes a process whereby well-heeled Brazilian teens set off with a backpack and a teddy bear to volunteer at the mother church in Australia, or study for a degree at Hillsong College. The college offers accredited undergraduate and postgraduate degrees in theology and ministry. As the book shows, this adventure is often experienced as uplifting. However, some of the volunteers, many of whom grew up with servants, are shocked to find themselves cleaning toilets in the homes of church leaders.

The shaming of the church began with the firing of Hillsong New York City’s hip pastor, Carl Lentz, for sexual misconduct in 2020. The US had been a happy celebrity hunting ground for the church. Lentz claimed to have baptised the pop star Justin Bieber in the bathtub of NBA player Tyson Chandler. Following the pastor’s removal, a four-part documentary, The Secrets of Hillsong, recounted a welter of further accusations against church members, including sexual misconduct, racial discrimination and labour exploitation.

In March 2022, the scandal finally reached Houston, who resigned from leadership of Hillsong following accusations of inappropriate behaviour with two female church members involving the abuse of alcohol and prescription medication. Houston remains unrepentant, quoting Proverbs 19:28 on Twitter/X: “An unprincipled witness desecrates justice; the mouths of the wicked spew malice.”

Rocha’s intriguing verdict is that, in Brazil, the fact that Hillsong was prepared to fire its founder was seen as proof that the church was transparent and ethical. Meanwhile, Hillsong continues to expand its reach in low- and middle-income countries, with global lead pastors Phil and Lucinda Dooley responsible for “planting” the church in South Africa. “Perhaps Hillsong has a brighter future in the global south than the global north,” Rocha concludes.

This article is from New Humanist’s winter 2024 issue. Subscribe now.