Ihsan Abdel Kouddous's classic novel - published in English for the first time - shines a light on politics and power in Egypt

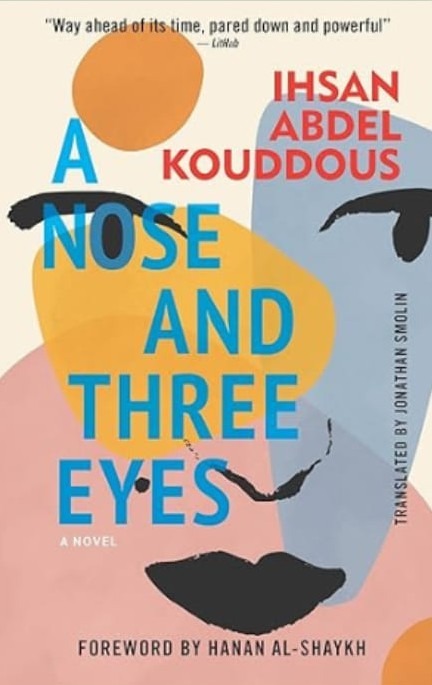

A Nose and Three Eyes (Hoopoe Books) by Ihsan Abdel Kouddous, translated by Jonathan Smolin

Egyptian author Ihsan Abdel Kouddous, who died in 1990, is one of the 20th century’s most prolific and popular writers of Arabic fiction. Born in Cairo in 1919, a contemporary of Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz, Abdel Kouddous also enjoyed a long career in journalism. He was editor at the daily paper Al-Akhbar and editor-in-chief of the political weekly magazine Rose El-Youssef. His bestselling novel A Nose and Three Eyes, deftly translated by Dartmouth professor Jonathan Smolin, is being published in English for the first time, despite having twice been adapted for Arabic-language films – in 1972 and 2024 – and produced for radio and television. The novel explores lust, love and deception in 1950s Egypt, while critiquing the regime of Gamal Abdel Nasser. According to Smolin’s enlightening introduction, some knowledge of Abdel Kouddous’s biography is necessary to fully appreciate the novel, and I’m inclined to agree.

Abdel Kouddous first rose to prominence as a writer in the 1940s, befriending Nasser and other Free Officers (nationalists in the armed forces, drawn from the ranks of the middle class, young workers and government officials) in the early 1950s. He used his position at Rose El-Youssef to uncover scandals among the ruling elite and to call for revolution. When King Farouk was eventually toppled in a coup d’état by the Free Officers Movement in July 1952, Abdel Kouddous was a prominent supporter of their reforms.

However, by January 1953 the writer realised that Nasser did not intend to hold democratic elections. A year later, annoyed by his former friend’s denunciations, Nasser imprisoned Abdel Kouddous for three months. On his release from jail, the editor turned to fiction, deciding to employ “the tools of metaphor and symbolism to retell his deeply fraught history with the revolution and dissent against Nasser”.

Like many of his previous novels, A Nose and Three Eyes was serialised in Rose El-Youssef. Abdel Kouddous would finish each chapter hours before it went to press, giving a sense of immediacy to the story. Smolin believes that “Ihsan’s relationship with Nasser – and Nasser’s romance with Egypt – provide a crucial lens through which to understand the work.” The novel’s main protagonist, the titular “nose”, is Dr Hashim, who is considered a “thinly veiled double of Nasser himself”. The eyes are three of his lovers, who represent “the three distinct phases of Nasser’s relationship with the nation” – first, the misplaced belief that he will overcome corruption, second, that he will heal Egypt, and finally his failed desire for pan-Arab unity.

In the autumn of 1963, Abdel Kouddous was seeing a young Lebanese woman, Hanan al-Shaykh, who went on to become a successful author herself (her novels in English translation include The Story of Zahra and Women of Sand and Myrrh). In her excellent foreword to this edition of A Nose and Three Eyes she confirms that she represents the novel’s third “eye”, embodying “a generation that believed in existentialism and modern society with progressive values”.

The first section of the novel is set in the early 1950s. After teenager Amina falls for Dr Hashim, she divorces her businessman husband, a representative of Egypt’s corrupt previous era and a man she has come to loathe. Amina believes that the sophisticated, eloquent, much older doctor will marry her, but he is a lothario, and Amina is eventually discarded.

The second eye is Nagwa Tahir, whose controlling mother turns her into a nervous wreck. When Dr Hashim treats her anxiety, they fall for one another. But Nagwa’s mother has already “sold” sexual rights to her daughter to the wealthy Uncle Abdu. The final part takes place in the late 50s as our protagonist pursues a young Lebanese woman, Rihab, who refuses to be confined by him. Smolin suggests their relationship provides “an obvious parallel for Nasser’s delusional infatuation with Syria in his failed romance with the United Arab Republic”.

While serialising the second eye, Abdel Kouddous was charged with “harming public morality”. He abruptly concluded the serialisation of the novel and left Egypt for the summer to allow things to cool down.

Even today, many may find the book’s themes unpalatable. Hashim repeatedly pursues younger women and exploits their infatuation with him. But reading the novel with its political context in mind, one realises that Abdel Kouddous was indeed challenging a deeply conservative society, and condemning the strictures and expectations faced by women.

A Nose and Three Eyes provides a fascinating entry into Egypt’s past, while also serving to illuminate how powerful men are able to abuse their position in order to dominate and assault women without censure. Plus ça change.

This article is from New Humanist’s Spring 2025 issue. Subscribe now.