Heresy: Jesus Christ and the Other Sons of God (Picador) by Catherine Nixey

Many of us suffer from the cognitive bias known as the “just world fallacy”. The sense that the world should be a fair place can easily slide into the belief that it is a fair place and that people generally get what they deserve. When it is applied to the victorious history of our own people or tribe, it implies that the events of the past were meant to be and were for the best.

One example of this is the Christian exceptionalism that seems to be thriving, as evidenced by recent popular works such as Tom Holland’s 2019 Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind. Broadly, this is the idea that Christianity in ancient times came as a unique blessing into a world that knew little kindness or compassion, being ignorant of universal notions of humanity. The suffering people of that time embraced the religion of Jesus Christ, with its promise of justice and equality, as an alternative to the chaotic polytheism under which they had previously laboured. From these roots in due course flowered all the values of the west: a unique and Christianity-dependent harvest.

In Heresy, Catherine Nixey strips these pretensions away with a complete (but scholarly) lack of mercy. Her focus is on Christianity’s first few centuries and she brings together three facts that are well known in the niche fields of ancient history and biblical studies, but not by the general reader, and rarely considered together.

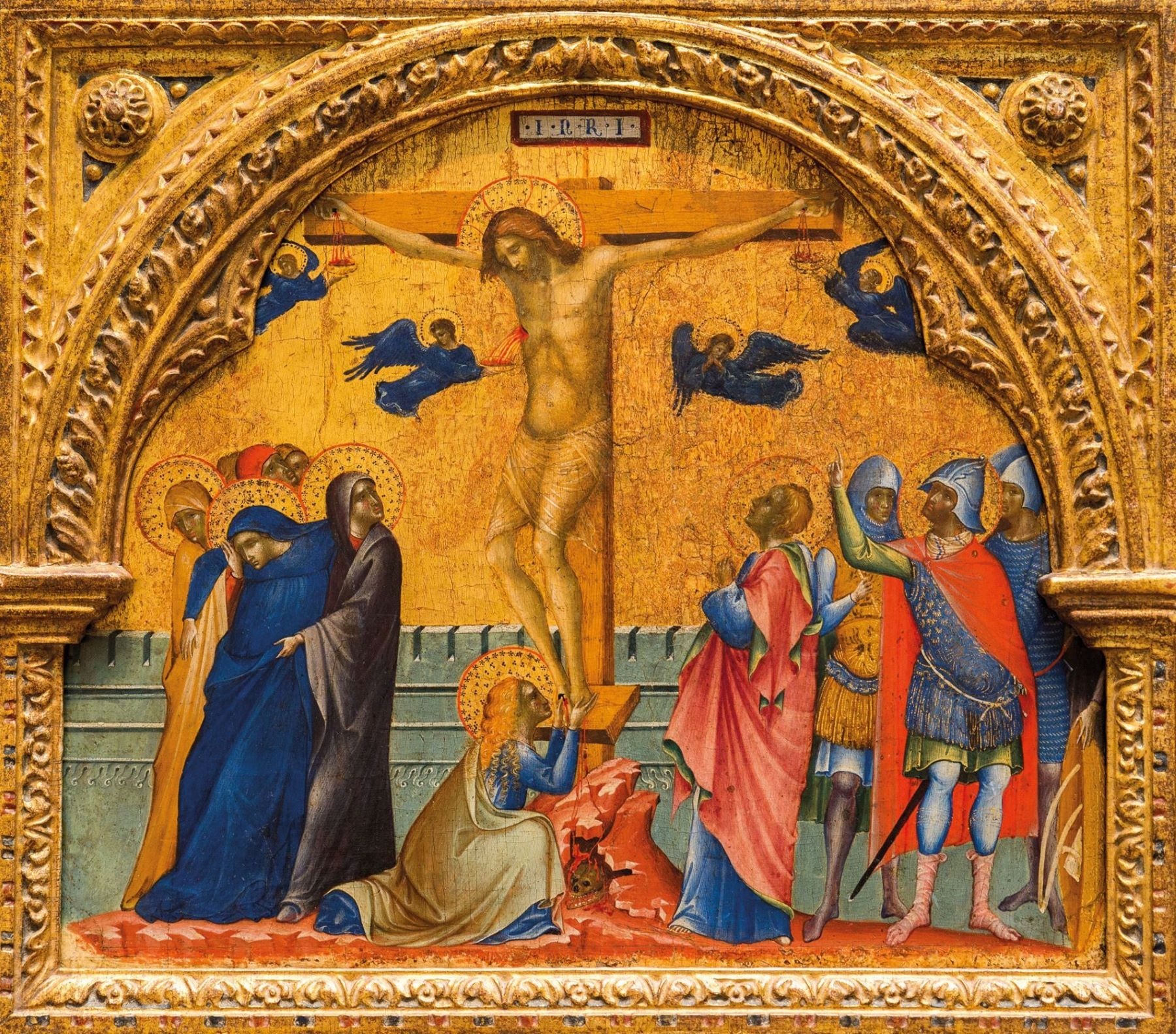

The first is that the figure of Jesus, far from being unique, was just one of many strikingly similar god-men and magicians around in the Roman Mediterranean, with some claiming to perform miracles that are near-identical to those described in the Bible. Walking on water, turning water into wine, healing the sick, raising the dead, feeding vast crowds with food conjured out of thin air, exorcising demons out of men – these were their staples. We have many texts now that show this. We also have multiple images of Jesus holding what appears to be a magic wand in early Christian art.

Second, the tales that have ended up in the modern Bible are just a small portion of the stories that early Christians believed – from the one about God’s breast being milked for the Holy Spirit, to the time the infant Jesus struck his school friends dead when they annoyed him. Today, we don’t know these stories because they were branded as the “heresies” that give Nixey’s book its powerful title.

The third is that many educated and virtuous people of the Roman world objected to the rise of Christianity as an irrational and immoral belief system. Nixey gives us fascinating quotes from the works of the philosophers Celsus and Porphyry and from the emperor Julian. Many of their points are similar to those made by non-Christian critics today: the nonsense of resurrection, the question of why God waited so long to send his son to Earth, the relative banality of Christianity’s moral precepts, even dressed up as radical ethics (“Is there any society that doesn’t have a law against murder?”, asks Julian.)

These three facts, taken together, highlight how incredibly contingent the emergence of Christianity was, and even more so the specific version that survived. Even if a similar monotheistic religion was always bound to have dominated the west for those centuries – which is not a given by any means – it still could have been the Jesus with a magic wand who prevailed, or one of the other god-men.

Classicists have long known that the Mediterranean world was full of miracles and magic, so why does Heresy still stand out as a shocking intervention? A lot is down to the conspiracy of silence (Nixey calls it a “gentlemen’s agreement”) between theologians on one side and classicists and ancient historians on the other. I once asked one of my ancient history tutors at university what he thought about the historical Jesus and he scoffed. “That’s myth – not history.” But you wouldn’t hear him saying that in his public lectures. Nixey’s book, therefore, breaks an important taboo. It’s a gripping and well-crafted mix of scholarship and polemic, and a challenge to any who still believe – whether they are religious or not – that Christianity was somehow fated to emerge and shape the west.

This article is from New Humanist’s autumn 2024 issue. Subscribe now.