Smoke and Ashes (John Murray) by Amitav Ghosh

As the UK gears up for elections, the Conservative Party is doubling down on their “tough on drugs” approach, including banning the sale of nitrous oxide (laughing gas), despite warnings from policy experts that it will increase health and social harms associated with the substance. But there is another reason the UK’s criminalisation of recreational drug users is highly ironic: not so long ago, imperial Britain was the largest drug dealer in the world. This history is the subject of Amitav Ghosh’s latest book, Smoke and Ashes: Opium’s Hidden Histories. The book recounts how the world’s first and biggest cross-continental traffic in opium – run by the most powerful European empires and led by Britain – claimed generations of colonised Asians as its victims, helping to create the unequal world order as we know it today.

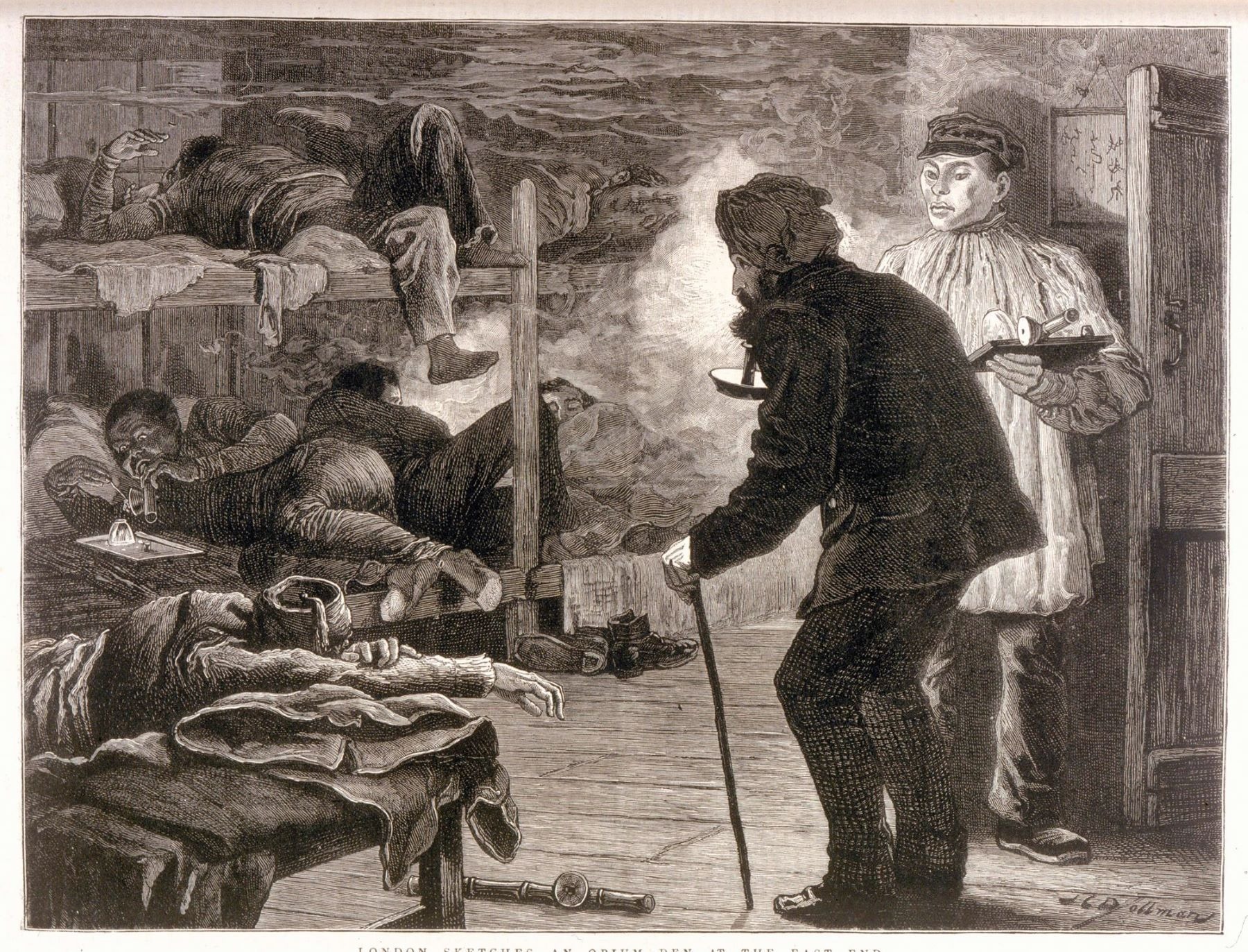

Ghosh begins the story of the colonial opium trade with the Portuguese and Dutch. Both countries used the drug as currency to facilitate trade flows, in a bid to acquire a mono-poly over Asian spices such as nutmeg, mace, clove and pepper. But it was the British who, a century later, chanced upon opium as a way to fund their growing imports of Chinese tea. In the process they perfected what Ghosh describes as “the model of the colonial narco state”. Under the British, an existing but small-scale trade grew exponentially, as the East India Company forced farmers in its newly acquired Indian colony to grow opium poppy over large tracts of land and smuggled the highly addictive smoking opium into China.

Soon, opium became one of the biggest sources of revenue for the British government and its colonial regime in India. Meanwhile, the drug-running operation impoverished millions of farmers and plunged generations of Chinese into addiction. When the Chinese state clamped down on this illegal trade in 1839 to protect its citizens, Britain waged two devastating wars that forced China to sign humiliating treaties, cede the island of Hong Kong and legalise British Indian opium for over half a century.

A fictional recreation of these events leading up to the First Opium War of 1840 was the subject of Ghosh’s Ibis trilogy. In Smoke and Ashes, the author takes the non-fiction route and casts a wider net. The book’s central argument is that the traffic in opium not only was crucial to the survival and expansion of the British and other European empires, but also partly laid the foundations of the globalised economy and modern capitalism.

The subject of opium imperialism has been explored by many authors in the past, but what sets Smoke and Ashes apart is how Ghosh brings the past in conversation with the present. By meticulously following a wealth of lesser-known and unusual archives that include the author’s own family history, colonial memoirs, travelogues, letters of opium traders, “Company paintings” and Chinese artefacts, Ghosh is able to show how the global flows of opium fuelled the rise of modern cities like Mumbai and Shanghai, and left its legacy in the world’s biggest corporations.

However, the most visible imprints of the older traffic in opium can be seen in the free-market ideologies of modern capitalism. Ghosh’s careful analysis demonstrates how the free-market logic touted by contemporary fossil fuel and mining companies to normalise rampant resource extraction is rooted in the doctrine deployed by private British traders to justify flooding China with smuggled opium.

This is perhaps most evident in the striking parallels Ghosh draws between the colonial opium trade and the American opioid crisis. The Sackler family and Purdue Pharma’s argument that their opioid drug Oxycontin was merely meeting an unmet demand and rarely led to addiction shares eerie similarities with British opium traffickers’ claims that demand already existed in China, and if they didn’t supply it, someone else would. Both logics allowed the perpetrators to disavow their role in deliberately creating a market for their drugs even as they shifted the blame for widespread addiction onto users and the forces of supply and demand.

Ultimately, Smoke and Ashes is yet another reminder of the devastation and exploitation perpetrated in the name of empire. The book is unwavering in its assertion that “the British empire’s opium racket was a criminal enterprise, utterly indefensible by the standards of its own time as well as ours”. Equally, by examining the abiding legacies of this drug racket, the book mounts a trenchant critique of unfettered globalisation, the hypocrisy of free markets and free trade, and the contemporary unequal world order.

This article is from New Humanist’s summer 2024 issue. Subscribe now.