Extremist, early 19th century: a person who holds extreme political or religious views, especially one who advocates illegal or violent action.

In 1809, a physician and opponent of vaccination by the name of Benjamin Moseley wrote, “In every country the subject has seized the ‘heat-oppressed brain’ of extremists only.” According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this was the first time the word “extremist” was used in written English.

The term seems to exclude the possibility that the “moderate middle” could ever itself be extreme. It is thus a spatial metaphor with which to describe our attitudes.

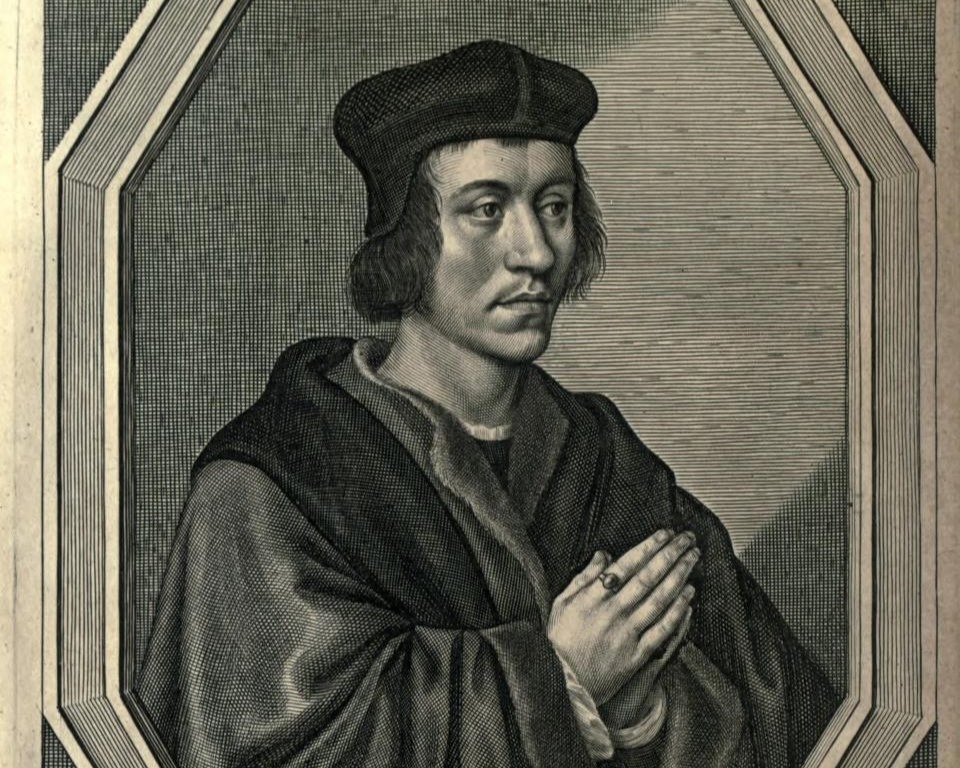

An early example of the geographical use is in one of the Acts of Henry VII, which talks of Chichester as being “in the extream Part of the … Shire” (1503). The first recorded use of “extreme” as an adjective is in a very modern sounding phrase, “Lyvyn in the most extreme Povertie”, which was used to describe the poor in Sir John Fortescue’s major work of early political science The Governance of England (c.1460). As you might guess, the word has a French origin, and before that, Latin: “extremus” meaning the most “outward” or “outermost”.

Today, the spatial metaphor is often used to describe political or religious views, as a means to categorise them as dangerous or abnormal. The British government has recently updated its definition of extremism as “the promotion or advancement of an ideology based on violence, hatred or intolerance, that aims to: 1) negate or destroy the fundamental rights and freedoms of others; or 2) undermine, overturn or replace the UK’s system of liberal parliamentary democracy and democratic rights; or 3) intentionally create a permissive environment for others to achieve the results in 1) or 2).”

This new definition is meant to be more “focused” and was accompanied by examples of supposedly extremist organisations: three Muslim and two far-right groups. That some of these groups have already rejected the definition proves there will always be disagreement about what falls inside, or outside of the norm.

This article is from New Humanist’s summer 2024 issue. Subscribe now.