From Soviet scientists to tech moguls, blood has been the subject of our wildest experiments

In March 1928, in Moscow, 53-year-old philosopher and scientist Alexander Bogdanov performed a blood transfusion. He transferred his own blood into a 21-year-old student, Lev Koldomasov, and that of the young man into himself. Initially the transfusion went well, but that evening Bogdanov began to suffer aches and pains throughout his body, as well as fever and vomiting. This was not surprising. Bogdanov had chosen the student because he was suffering from tuberculosis and malaria. For several years Bogdanov had been experimenting in transferring blood between people, including his wife, various students – and even Lenin’s sister.

Bogdanov was no crank. He was one of the great philosophers of Soviet Russia, and a close ally of Lenin’s at the beginning of the Bolshevik movement; there is a possible alternative history in which he would have been their leader. But it was to the question of blood that he was to devote the last years of his life. His basic aim was simple: he wanted to slow down and possibly even stop the ageing process. He thought he had worked out a way to turn back the human clock. Mutual blood transfusion. It was altruistic. It was collective. It was, he thought, Marxist.

On 7 April, it killed him. But the idea did not die with Bogdanov. From its socialist roots, we are seeing the same effort pursued today at the extreme end of capitalism, by tech billionaires and longevity enthusiasts, whose aims are not always quite so altruistic.

A very special substance

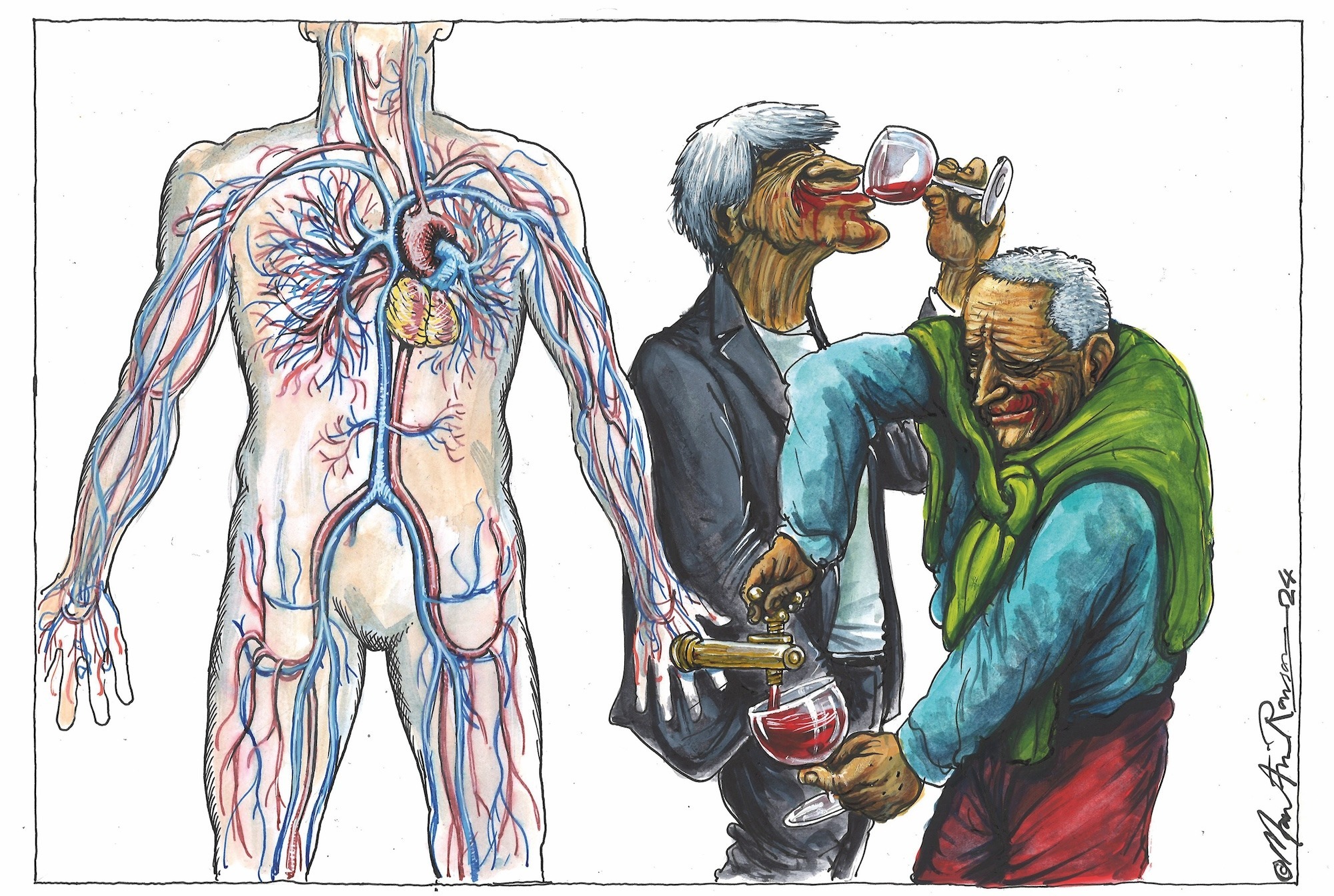

Blood. A baby contains a cup of it, an average human around five litres. Throughout human existence it has been loaded with social, cultural and religious significance. It gives us strength. We spill it for our country. We use it for sacrifices and ritual. We drink the blood of Christ. It invokes elemental fears – ticks, leeches and mosquitos are “blood suckers”. Not to mention vampires.

It was the English physician William Harvey who gave the first full description of the circulation of blood in 1628. Previously it had been believed that blood was produced in the body, the liver being the usual candidate, while being consumed at the same rate as a form of nutrient. Harvey found it improbable that the liver could produce so much blood – five litres per minute – so consistently. His insight was that no new blood was being produced. It was the same blood over and over again. Or, as Harvey put it in the self-effacing language of the academic, “There must be a motion, as it were, in a circle.” This meant that the heart could now be regarded as simply a pump for moving liquid around – a piece of machinery, albeit an ingenious one.

If this was a type of demystification, it wasn’t long before new mysticisms were rushing in to fill the space. If blood was simply a liquid, could it not be replaced with another substance, for instance in the case of massive blood loss? Or might a better liquid be found, which would lead to a longer life? The craze for answering such questions swept through the scientific community, and the non-scientific too. Attempts to replace blood with other substances proved unpromising. Blood seemed to need to be replaced with blood. So the next question was, could it be transferred – from person to person, animal to animal, or even from species to species?

Soon after Harvey’s publication, transfusion became a proper object of scientific study. The first animal-to-animal transfusion, between two dogs, was carried out by Richard Lower in 1665. Two years later in France, the physician of Louis XIV, Jean-Baptiste Denys, seeking a viable source of blood for those who had lost it, performed the first animal-to-human transfusion, transferring the blood of a sheep to a 15-year-old boy, who survived. Although the quantity of blood transferred was tiny (thus preventing the sorts of complication familiar to us now), Denys was encouraged to continue. Unfortunately his next two subjects, into whom he transferred calf’s blood, both died.

Seeking transformation

Back in Britain and undeterred by Denys’s failure, Lower transferred lamb’s blood into a man named Arthur Coga, a 32-year-old graduate of Cambridge University, who was “the subject of a harmless form of insanity”. It was felt that the gentleness of the lamb would be transferred to Coga, whose insanity manifested in a “tempestuous character”. For the first time in the medical domain, the idea of transfusion was coupled with the possibility of supra-sanguine effects. (Coga himself later wrote to the Royal Society to complain that he had in fact been transformed into a sheep and, now unemployable, had begun pawning his clothes, or “Golden Fleece”. He signed the letter “Agnus Coga” – Coga the Sheep.)

This new way of seeing the body as mechanical in design coincided with philosophical ideas concerning the transformation of humans – “upgrades”, as it were. No less a thinker than René Descartes, in his Discourse on Method (1637), posited a future where humans would remain vigorous and healthy for ever, while in his 1793 text Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, the English philosopher William Godwin – father of Mary Shelley – argued for the possibility of “earthly immortality”.

But it wasn’t until 1818 that the first human-to-human transfusion was carried out. British obstetrician James Blundell wished to help his patients, many of whom were dying of postpartum haemorrhage. Using one patient’s husband as a donor, he was able to save a woman’s life, and would carry out 10 more such operations over the next few years, making himself a millionaire in the process.

Throughout the 19th century, the experiments continued, with varying degrees of success. Most ended in failure, and the failures were mysterious – they seemed to follow no discernible pattern. It was only the discovery of “blood types” by the Austrian physician Karl Landsteiner in 1900 that solved the mystery, although it would be another 28 years before our current classification system (O, A, B, negatives and positives, and so on) was adopted.

Everything was in place. Enter Alexander Bogdanov and the Soviet Cosmists.

Blood, betrayal and the Bolsheviks

Born Alexander Malinovsky in 1873, he had, as was the trend in early Bolshevik circles, changed his name to something more exotic. Bogdanov read Marx young, Lenin in his early 20s, and with the latter co-founded the Bolsheviks in 1903. For the next six years his influence in the party was second only to Lenin’s, and they worked side by side, producing pamphlets, giving speeches – even planning bank robberies together.

Their split was both arcane in its subject matter and magnificent in revealing how much was at stake in early Soviet thinking. Bogdanov’s philosophical work attempted to resolve the notoriously tortuous question of the relationship between subject (the human) and object (the outside world). He called his solution empirio-criticism, and it argued that the world can only be apprehended by experience. We cannot posit a world outside our own subjectivity, so the objects of the world can only be approached as objects of consciousness. It was a denial of duality, an embrace of unity.

This was an anathema to Lenin, for whom the material world – objects outside the mind – was fundamental. It is, he argued, material conditions that form the human. Marx said so. His response to Bogdanov’s position was the long and very shouty Materialism and Empirio-Criticism (1908) in which he accused Bogdanov of the ultimate thought-crime: falling prey to metaphysical idealism. Bogdanov was expelled from the party he had helped to create.

But Bogdanov was not to be dissuaded from his ideas, and went deeper into them, attempting to formulate a universal science by seeking the organisational principles that underly all systems. He called it tektology. His work Tektology: Universal Organisation Science, published in three volumes from 1912 to 1917, proposed a sort of proto-structuralism, anticipating many of the ideas in what is now known as systems theory. For all the differentiation in parts of a system, there was a basic structure which held it together, and a change in one part affected the whole.

It is in his later Essays in Tektology (1922) that Bogdanov first explored the relationship between his ideas and the question of ageing. All previous attempts to tackle this “disease” had treated it as any other illness – analysing the symptoms, and prescribing various cures for each one. But tackling each symptom separately was only a partial intervention. Old age was a totality.

What was needed was, as we would say now – and Bogdanov in fact said then – a “holistic” approach. Only in blood transfusion, he argued, is the whole self intertwined with that of another; and then only if the transfusion is two-way, a “simultaneous interchanging transfusion, from individual A to individual B, and from B to A”. Two bloods exchanged will have their own strengths and weaknesses, developed over the course of each of their lives, which will then be gifted to the other person.

For Bogdanov, the ne plus ultra of such an exchange was that between older and younger individuals. The young blood would help the older individual “with their struggles”. But wouldn’t the old blood age the young? No, because “the strength of youth consists in its enormous ability of assimilation and transformation” – it would fight off the detrimental effects. And the gift for the young would be all the immunity that the older subject had built up.

Not only that but “from an organisational point of view” this would cause “a positive increase in the sum of elements for evolution”. Over time, the whole human race would gain an advantage. Bogdanov did grudgingly acknowledge that there might be problems. “It is clear,” he wrote at the end of the essay, “that the indicated path is full of difficulties and even dangers”, including “the possibility of transmission of illnesses”. As we have seen, in this he was prophetic.

Transhumanism, then and now

As Michel Eltchaninoff describes in his recent Lenin Walked on the Moon: The Mad History of Russian Cosmism, Bogdanov’s experiments were part of a particularly Soviet form of utopianism. Cosmism, a cultural and philosophical movement, proposed that humans had an ethical obligation not only to heal the sick, but to vanquish death. This interest in the transformation of the physical self encompassed interplanetary travel, as this might facilitate eternal life, or even the resurrection of the dead. Eltchaninoff argues that these Soviet thinkers can be seen as precursors of transhumanism.

Transhumanists seek to modify humans through technology. It is a growing field in both medicine – where advances in genetics, robotics and AI have led to major breakthroughs in tackling disease and injury – and philosophy, where the implications of “modified humans” are explored in terms of epistemology (what it means to be human) and ethics. For example, is the use of brain-computer interfaces (see page 42) ethically justifiable?

Some philosophers have embraced transhumanism wholeheartedly. The German philosopher Stefan Lorenz Sorgner, in his 2021 book We Have Always Been Cyborgs, speaks of humans as “carbon-based transhuman technologies” which fit his definition of cyborgs – “a governed, a steered organism”.

The British philosopher Max More calls transhumanism the “continuation and acceleration of the evolution of intelligent life beyond its currently human form and human limitations by means of science and technology, guided by life-promoting principles and values”. But these ideas have not just found sympathy in philosophical circles. They have gained huge traction among the super-rich (see page 18). Elon Musk and Google co-founder Sergey Brin are just two of the better-known tech moguls interested in transhumanist thought, which positions the domination of space and the pursuit of longevity as expressions of human uniqueness and liberty. More’s philosophy of extropianism, which focuses on self-improvement while espousing small government, individual rights and the protection of “people’s freedom to experiment, innovate, and progress”, dovetails with many of the goals of these entrepreneurs of the transhuman.

One common goal of transhumanists is, unsurprisingly, to defy death. Tech billionaire Bryan Johnson estimated in a 2024 interview that he spent $2 million a year on attempting to halt and reverse the ageing process. He takes 80 vitamins and minerals a day, eats 70 pounds of pureed vegetables a month, has taken 33,000 images of his bowels and has 30 doctors at his beck and call. He also recently transferred a litre of blood from his 17-year-old son into his own body, and donated a litre of his own blood to his 80-year-old father. He seems to believe, as Bogdanov had a century earlier, that younger blood would be beneficial. The project was scrapped as “no benefits were detected” but Johnson hasn’t ruled out further attempts.

Meanwhile, the startup company Ambrosia, created by Jesse Karmazin, a medical school graduate without a licence to practise medicine, began selling “young blood transfusions” for $8,000 in 2016. Banned in 2019, it is still a hot topic on such sites as lifespan.io (“crowdsourcing the cure for aging”), while other private providers are seeking to have the practice legalised. As with Johnson’s experiments, while benefits for humankind are touted, it is generally an extreme form of individualism that is front and centre.

Morals and motivations

To Bogdanov, his experiments with blood transfusions were a form of socialism. As much as he wished to gain an advantage by young blood being transferred into him, it was his hope that Lev Koldomasov’s ailing body would utilise the immunity he had developed over his longer life. In fact, Koldomasov made a full recovery – he lived until the mid-1980s, shortly before the end of the USSR. He would go on to spend his own life tackling the future – as a climatologist.

The sort of utilitarian motivation of Bogdanov seems radically absent from many of the would-be immortals of today. Transhumanists seem not to dream of a future in which all of humankind benefits equally from the advances they imagine making and being made. Theirs is a world, it seems, of perfected individualism, along recognisably capitalist lines, and with recognisably capitalist fissures that separate the worthy from the unworthy – or, to use blunter words, the rich from the poor.

Insofar as these are fantasies, they are, in a sense, exactly what one would predict from the sort of culture in which these people continue to acquire more and more command over life and death. But it can only be hoped – and with some confidence – that their final victory will remain just that: a fantasy.

This article is from New Humanist’s winter 2024 issue. Subscribe now.