Shaparak Khorsandi finds joy and chaos on the slopes

When people used to ask me, “Do you ski?” I always thought it was the same as asking, “Do you fly the trapeze?” or “Do you perform skull surgery?” Of course I didn’t. I never knew much about skiing other than that it was enjoyed by people who had organisational skills, finances and a death wish I simply did not possess. I liked relatively safe holidays, ones where returning home with unbroken limbs was expected, and not celebrated as a “win”.

But last summer, I accidentally wandered on to a WhatsApp group with parents from my daughter’s school who were planning an epic ski trip to France. About 25 families were going, all friends and neighbours – some I knew well, some not at all. Before I could work out how to leave the group, I was committed. A middle-aged woman who can’t walk down a slight slope without fearing injury now found herself paying to tie sticks to her feet and slide down a mountain.

I quickly learned that there is more admin involved in a skiing holiday than there was in Brexit. There were times when it all got so much that I lay weeping across my kitchen table. Kind friends had to explain how I had to hire a car, as walking from the airport to the resort would take three days. But eventually skis were hired, appropriate clothing borrowed, lift passes bought and lessons booked. As I watched the money drain from my account, I told myself it would be a wonderful experience with my teenage son and tween daughter. They would forever have beautiful memories of gliding effortlessly down a glistening mountain with their chic mother, at one with nature.

As it turned out, I barely caught a glimpse of my offspring the entire time we were there. They took to it like ducks to water, whizzing off with the rest of the class, while their mother clung to an instructor’s hand. I struggled to balance, even though I am 5’2” with size eight feet, which actually makes me a very close relative of the Emperor Penguin.

The instructor, Michèal, tried his best. He eventually weaned me off his hand and got me to hold on to his ski stick. But unfortunately, I proved too immature to cope with a French man demanding “Shappeee! ’Old my pole!” without giggling and falling arse over tit again. In the end, I was politely kicked out of ski school.

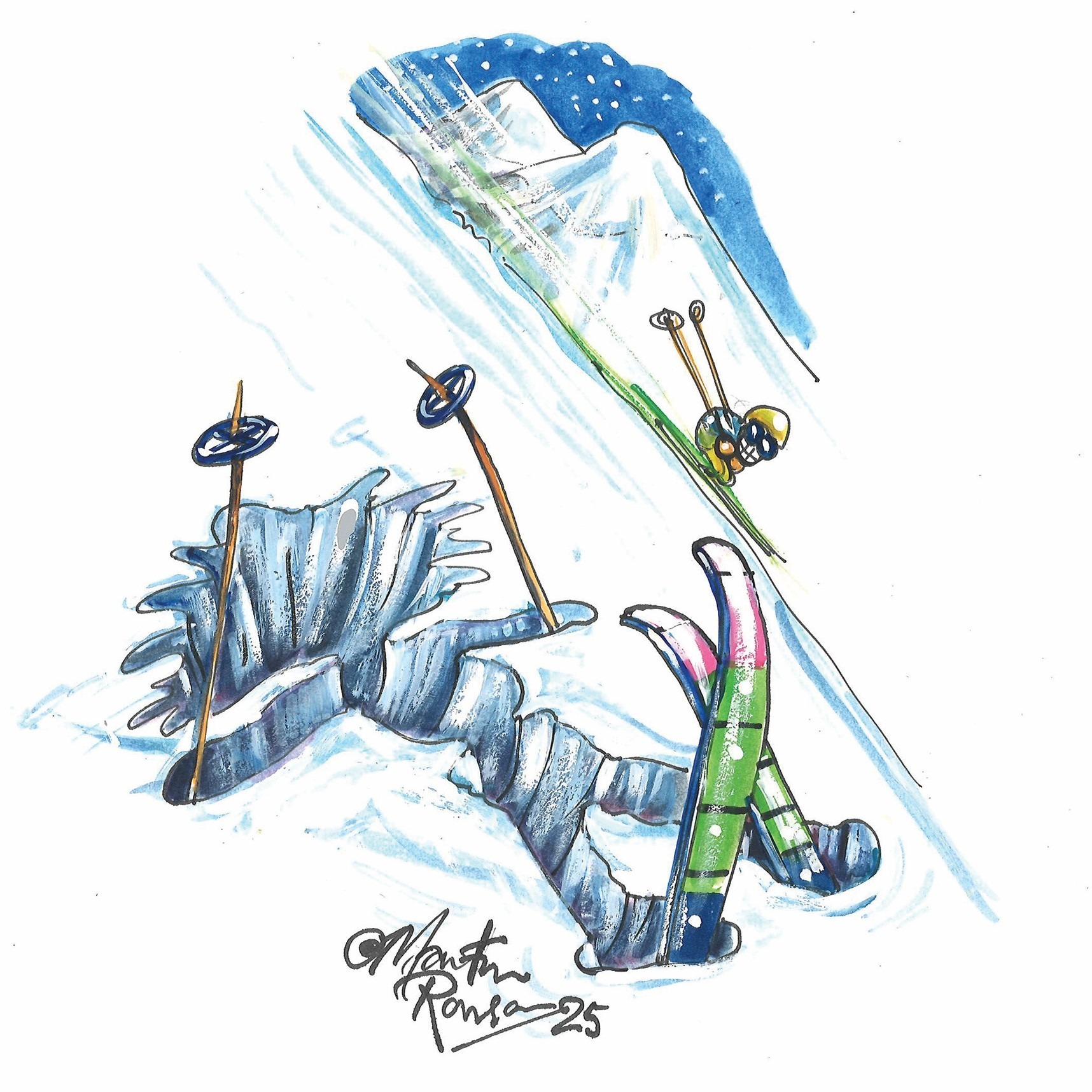

Friends took me up instead. It was more fun, but equally humiliating. There were moments when I simply couldn’t get back up and they had to quickly move me to the side for the safety of others, as though I was a hay bale that had fallen off the back of a tractor. I ended up in contortions with people from the WhatsApp group. I definitely became closer to some of my neighbours. How can you not when you have accidentally wrapped your leg around their husband’s neck in front of them?

After three days of being both Laurel and Hardy on the mountain, I sobbed and gave up. It was fascinating, watching the others enjoy this bonkers activity. These same people had often said to me, “You are so brave doing standup comedy, I could never do what you do.” But the humiliation of dying on stage is nothing compared to being a 51-year-old falling on your arse on the slopes, and a six-year-old going at 80 miles per hour stopping to check if you’re okay.

I had been judgemental about the types that skied, but they are thrill seekers like me. It’s mad to ski and risk injury. It also takes a kind of madness to die on your arse in front of an audience and then insist on doing it again and again until you’re half good – knowing that even then, the risk never goes away. The joy when it works is worth it.

It’s been a month or two since we got back. Out dog walking, I bumped into one of my neighbours who had been on the trip. “Are you going to come again next year, Shappi?” she asked. I looked at her in horror and replied, “Of course I bloody am.”

This article is from New Humanist’s Summer 2025 issue. Subscribe now.